Appendix A List of Acronyms¶

BYOD |

Bring Your Own Device |

CRADA |

Cooperative Research and Development Agreement |

EMM |

Enterprise Mobility Management |

FIPS |

Federal Information Processing Standards |

IBM |

International Business Machines |

ICS |

Industrial Control System |

iOS |

iPhone Operating System |

IP |

Internet Protocol |

ITL |

Information Technology Laboratory |

MDM |

Mobile Device Management |

NCCoE |

National Cybersecurity Center of Excellence |

NICE |

National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education |

NIST |

National Institute of Standards and Technology |

NISTIR |

NIST Interagency Report |

OS |

Operating System |

PII |

Personally Identifiable Information |

PIN |

Personal Identification Number |

PRAM |

Privacy Risk Assessment Methodology |

RMF |

Risk Management Framework |

SC |

Systems and Communications Protection |

SMS |

Short Message Service |

SP |

Special Publication |

URL |

Uniform Resource Locator |

VPN |

Virtual Private Network |

Appendix B Glossary¶

Access Management |

Access Management is the set of practices that enables only those permitted the ability to perform an action on a particular resource. The three most common Access Management services you encounter every day perhaps without realizing it are: Policy Administration, Authentication, and Authorization [S11]. |

Availability |

Ensure that users can access resources through remote access whenever needed [S12]. |

Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) |

A non-organization-controlled telework client device [S12]. |

Confidentiality |

Ensure that remote access communications and stored user data cannot be read by unauthorized parties [S12]. |

Data Actions |

System operations that process PII [S13]. |

Disassociability |

Enabling the processing of PII or events without association to individuals or devices beyond the operational requirements of the system [S13]. |

Eavesdropping |

An attack in which an attacker listens passively to the authentication protocol to capture information which can be used in a subsequent active attack to masquerade as the claimant [S14] (definition located under eavesdropping attack). |

Firewall |

Firewalls are devices or programs that control the flow of network traffic between networks or hosts that employ differing security postures [S15]. |

Integrity |

Detect any intentional or unintentional changes to remote access communications that occur in transit [S12]. |

Manageability |

Providing the capability for granular administration of PII including alteration, deletion, and selective disclosure [S13]. |

Mobile Device |

A portable computing device that: (i) has a small form factor such that it can easily be carried by a single individual; (ii) is designed to operate without a physical connection (e.g., wirelessly transmit or receive information); (iii) possesses local, non-removable or removable data storage; and (iv) includes a self-contained power source. Mobile devices may also include voice communication capabilities, on-board sensors that allow the devices to capture information, and/or built-in features for synchronizing local data with remote locations. Examples include smart phones, tablets, and E-readers [S10]. |

Personally Identifiable Information (PII) |

Any information about an individual maintained by an agency, including any information that can be used to distinguish or trace an individual‘s identity, such as name, Social Security number, date and place of birth, mother‘s maiden name, or biometric records; and any other information that is linked or linkable to an individual, such as medical, educational, financial, and employment information [S16] (adapted from Government Accountability Office Report 08-536). |

Problematic Data Action |

A data action that could cause an adverse effect for individuals [S2]. |

Threat |

Any circumstance or event with the potential to adversely impact organizational operations (including mission, functions, image, or reputation), organizational assets, individuals, other organizations, or the Nation through an information system via unauthorized access, destruction, disclosure, or modification of information, and/or denial of service [S8]. |

Vulnerability |

Weakness in an information system, system security procedures, internal controls, or implementation that could be exploited by a threat source [S8]. |

Appendix C References¶

- S1

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). NIST Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity, Version 1.1 (Cybersecurity Framework). Apr. 16, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.nist.gov/cyberframework.

- S2(1,2)

NIST. NIST Privacy Framework: A Tool for Improving Privacy Through Enterprise Risk Management, Version 1.0 (Privacy Framework). Jan. 16, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.nist.gov/privacy-framework.

- S3

W. Newhouse et al., National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education (NICE) Cybersecurity Workforce Framework, NIST Special Publication (SP) 800-181 rev. 1, NIST, Gaithersburg, Md., Nov. 2020. Available: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-181r1.pdf.

- S4

NIST. Risk Management Framework (RMF) Overview. [Online]. Available: https://csrc.nist.gov/projects/risk-management/risk-management-framework-(rmf)-overview.

- S5

NIST. Mobile Threat Catalogue. [Online]. Available: https://pages.nist.gov/mobile-threat-catalogue/.

- S6

NIST. NIST Privacy Risk Assessment Methodology. Jan. 16, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.nist.gov/privacy-framework/nist-pram.

- S7

Joint Task Force, Risk Management Framework for Information Systems and Organizations: A System Life Cycle Approach for Security and Privacy, NIST SP 800-37 Revision 2, NIST, Gaithersburg, Md., Dec. 2018. Available: https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/sp/800-37/rev-2/final.

- S8(1,2,3,4)

Joint Task Force Transformation Initiative, Guide for Conducting Risk Assessments, NIST SP 800-30 Revision 1, NIST, Gaithersburg, Md., Sept. 2012. Available: https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/sp/800-30/rev-1/final.

- S9

NIST. Minimum Security Requirements for Federal Information and Information Systems, Federal Information Processing Standards Publication (FIPS) 200, Mar. 2006. Available: https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/fips/200/final.

- S10

Joint Task Force Transformation Initiative, Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations, NIST SP 800-53 Revision 5, NIST, Gaithersburg, Md., Sept. 2020. Available: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-53r5.pdf.

- S11

IDManagement.gov. “Federal Identity, Credential, and Access Management Architecture.” [Online]. Available: https://arch.idmanagement.gov/services/access/.

- S12(1,2,3,4)

M. Souppaya and K. Scarfone, Guide to Enterprise Telework, Remote Access, and Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) Security, NIST SP 800-46 Revision 2, NIST, Gaithersburg, Md., July 2016. Available: https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/sp/800-46/rev-2/final.

- S13(1,2,3,4)

S. Brooks et al., An Introduction to Privacy Engineering and Risk Management in Federal Systems, NIST Interagency or Internal Report 8062, Gaithersburg, Md., Jan. 2017. Available: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ir/2017/NIST.IR.8062.pdf.

- S14

P. Grassi et al., Digital Identity Guidelines, NIST SP 800-63-3, NIST, Gaithersburg, Md., June 2017. Available: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-63-3.pdf.

- S15

K. Stouffer et al., Guide to Industrial Control Systems (ICS) Security, NIST SP 800-82 Revision 2, NIST, Gaithersburg, Md., May 2015. Available: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-82r2.pdf.

- S16

E. McCallister et al., Guide to Protecting the Confidentiality of Personally Identifiable Information (PII), NIST SP 800-122, NIST, Gaithersburg, Md., Apr. 2010. Available: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/Legacy/SP/nistspecialpublication800-122.pdf.

- S17

J. Franklin et al., Mobile Device Security: Corporate-Owned Personally-Enabled (COPE), NIST SP 1800-21, NIST, Gaithersburg, Md., July 22, 2019. Available: https://csrc.nist.gov/News/2019/NIST-Releases-Draft-SP-1800-21-for-Comment.

- S18

NIST, NIST Interagency Report (NISTIR) 8170, Approaches for Federal Agencies to Use the Cybersecurity Framework, Mar. 2020. [Online]. Available: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ir/2021/NIST.IR.8170-upd.pdf.

Appendix D A Note Regarding Great Seneca Accounting¶

A description of a fictional organization, Great Seneca Accounting, was included in the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication (SP) 1800-22 Mobile Device Security: Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) Practice Guide.

This fictional organization demonstrates how a small-to-medium sized, regional organization implemented the example solution in this practice guide to assess and protect their mobile-device-specific security and privacy needs. It illustrates how organizations with office-based, remote-working, and travelling personnel can be supported in their use of personally owned devices that enable their employees to work while on the road, in the office, at customer locations, and at home.

Figure D-1 Great Seneca Accounting’s Work Environments

Appendix E How Great Seneca Accounting Applied NIST Risk Management Methodologies¶

This practice guide contains an example scenario about a fictional organization called Great Seneca Accounting. The example scenario shows how to deploy a Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) solution to be in alignment with an organization’s security and privacy capabilities and objectives.

The example scenario uses National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) standards, guidance, and tools. It is provided in the Example Scenario: Putting Guidance into Practice supplement of this practice guide.

This appendix provides a brief description of some of the key NIST tools referenced in the example scenario supplement of this practice guide.

Section E.1 below provides descriptions of the risk frameworks and tools, along with a high-level discussion of how Great Seneca Accounting applied each framework or tool in the example scenario. Section E.2 describes how the NIST Cybersecurity Framework and NIST Privacy Framework can be used to establish or improve cybersecurity and privacy programs.

E.1 Overview of Risk Frameworks and Tools That Great Seneca Used¶

Great Seneca used NIST frameworks and tools to identify common security and privacy risks related to BYOD solutions and to guide approaches to how they were addressed in the architecture described in Volume B Section 4. Great Seneca used additional standards and guidance, listed in Appendix D of Volume B, to complement these frameworks and tools when designing their BYOD architecture.

Both the Cybersecurity Framework and Privacy Framework include the concept of framework profiles, which identify the organization’s existing activities (contained in a Current Profile) and articulate the desired outcomes that support its mission and business objectives within its risk tolerance (that are contained in the Target Profile). When considered together, Current and Target Profiles are useful tools for identifying gaps and for strategic planning.

E.1.1 Overview of the NIST Cybersecurity Framework¶

Description: The NIST Cybersecurity Framework “is voluntary guidance, based on existing standards, guidelines, and practices for organizations to better manage and reduce cybersecurity risk. In addition to helping organizations manage and reduce risks, it was designed to foster risk and cybersecurity management communications amongst both internal and external organizational stakeholders.” [S17]

Application: This guide refers to two of the main components of the Cybersecurity Framework: The Framework Core and the Framework Profiles. As described in Section 2.1 of the Cybersecurity Framework, the Framework Core provides a set of activities to achieve specific cybersecurity outcomes, and reference examples of guidance to achieve those outcomes (e.g., controls found in NIST Special Publication [SP] 800-53). Section 2.3 of the Cybersecurity Framework identifies Framework Profiles as the alignment of the Functions, Categories, and Subcategories (i.e., the Framework Core) with the business requirements, risk tolerance, and resources of the organization.

The Great Seneca Accounting example scenario assumed that the organization used the Cybersecurity Framework Core and Framework Profiles, specifically the Target Profiles, to align cybersecurity outcomes and activities with its overall business/mission objectives for the organization. In the case of Great Seneca Accounting, its Cybersecurity Framework Target Profile helps program owners and system architects understand business and mission-driven priorities and the types of cybersecurity capabilities needed to achieve them. Great Seneca Accounting also used the NIST Interagency Report (NISTIR) 8170, The Cybersecurity Framework, Implementation Guidance for Federal Agencies [S18], for guidance in using the NIST Cybersecurity Framework.

E.1.2 Overview of the NIST Privacy Framework¶

Description: The NIST Privacy Framework is a voluntary enterprise risk management tool intended to help organizations identify and manage privacy risk and build beneficial systems, products, and services while protecting individuals’ privacy. It follows the structure of the NIST Cybersecurity Framework to facilitate using both frameworks together [S2].

Application: This guide refers to two of the main components of the Privacy Framework: The Framework Core and Framework Profiles. As described in Section 2.1 of the Privacy Framework, the Framework Core provides an increasingly granular set of activities and outcomes that enable dialog about managing privacy risk as well as resources to achieve those outcomes (e.g., guidance in NISTIR 8062, An Introduction to Privacy Engineering and Risk Management in Federal Systems [S13]). Section 2.2 of the Privacy Framework identifies Framework Profiles as the selection of specific Functions, Categories, and Subcategories from the core that an organization has prioritized to help it manage privacy risk.

Great Seneca Accounting used the Privacy Framework as a strategic planning tool for its privacy program as well as its system, product, and service teams. The Great Seneca Accounting example scenario assumed that the organization used the Privacy Framework Core and Framework Profiles, specifically Target Profiles, to align privacy outcomes and activities with its overall business/mission objectives for the organization. Its Privacy Framework Target Profile helped program owners and system architects to understand business and mission-driven priorities and the types of privacy capabilities needed to achieve them.

E.1.3 Overview of the NIST Risk Management Framework¶

Description: The NIST Risk Management Framework (RMF) “provides a process that integrates security and risk management activities into the system development life cycle. The risk-based approach to security control selection and specification considers effectiveness, efficiency, and constraints due to applicable laws, directives, Executive Orders, policies, standards, or regulations” [19]. Two of the key documents that describe the RMF are NIST SP 800-37 Revision 2, Risk Management Framework for Information Systems and Organizations: A System Life Cycle Approach for Security and Privacy; and NIST SP 800-30, Guide for Conducting Risk Assessments.

Application: The RMF has seven steps: Prepare, Categorize, Select, Implement, Assess, Authorize, and Monitor. These steps provide a method for organizations to characterize the risk posture of their information and systems and identify controls that are commensurate with the risks in the system’s environment. They also support organizations with selecting beneficial implementation and assessment approaches, reasoning through the process to understand residual risks, and monitoring the efficacy of implemented controls over time.

The Great Seneca Accounting example solution touches on the risk assessment activities conducted under the Prepare step, identifying the overall risk level of the BYOD system architecture in the Categorize step, and, consistent with example approach 8 in NISTIR 8170, reasoning through the controls that are necessary in the Select step. The influence of the priorities provided in Great Seneca Accounting’s Cybersecurity Framework Target Profile is also briefly mentioned regarding making decisions for how to apply controls during Implement (e.g., policy versus tools), how robustly to verify and validate controls during Assess (e.g., document review versus “hands on the keyboard” system testing), and the degree of evaluation required over time as part of the Monitor step.

E.1.4 Overview of the NIST Privacy Risk Assessment Methodology¶

Description: The NIST Privacy Risk Assessment Methodology (PRAM) is a tool for analyzing, assessing, and prioritizing privacy risks to help organizations determine how to respond and select appropriate solutions. A blank version of the PRAM is available for download on NIST’s website.

Application: The PRAM uses the privacy risk model and privacy engineering objectives described in NISTIR 8062 to analyze for potential problematic data actions. Data actions are any system operations that process data. Processing can include collection, retention, logging, analysis, generation, transformation or merging, disclosure, transfer, and disposal of data. A problematic data action is one that could cause an adverse effect, or problem, for individuals. The occurrence or potential occurrence of problematic data actions is a privacy event. While there is a growing body of technical privacy controls, including those found in NIST SP 800-53, applying the PRAM may result in identifying controls that are not yet available in common standards. This makes it an especially useful tool for managing risks that may otherwise go unaddressed.

The Great Seneca Accounting example solution assumed that a PRAM was used to identify problematic data actions and mitigating controls for employees. The controls in this build include some technical controls, such as controls that can be handled by security capabilities, as well as policy and procedure-level controls that need to be implemented outside yet are supported by the system.

E.2 Using Frameworks to Establish or Improve Cybersecurity and Privacy Programs¶

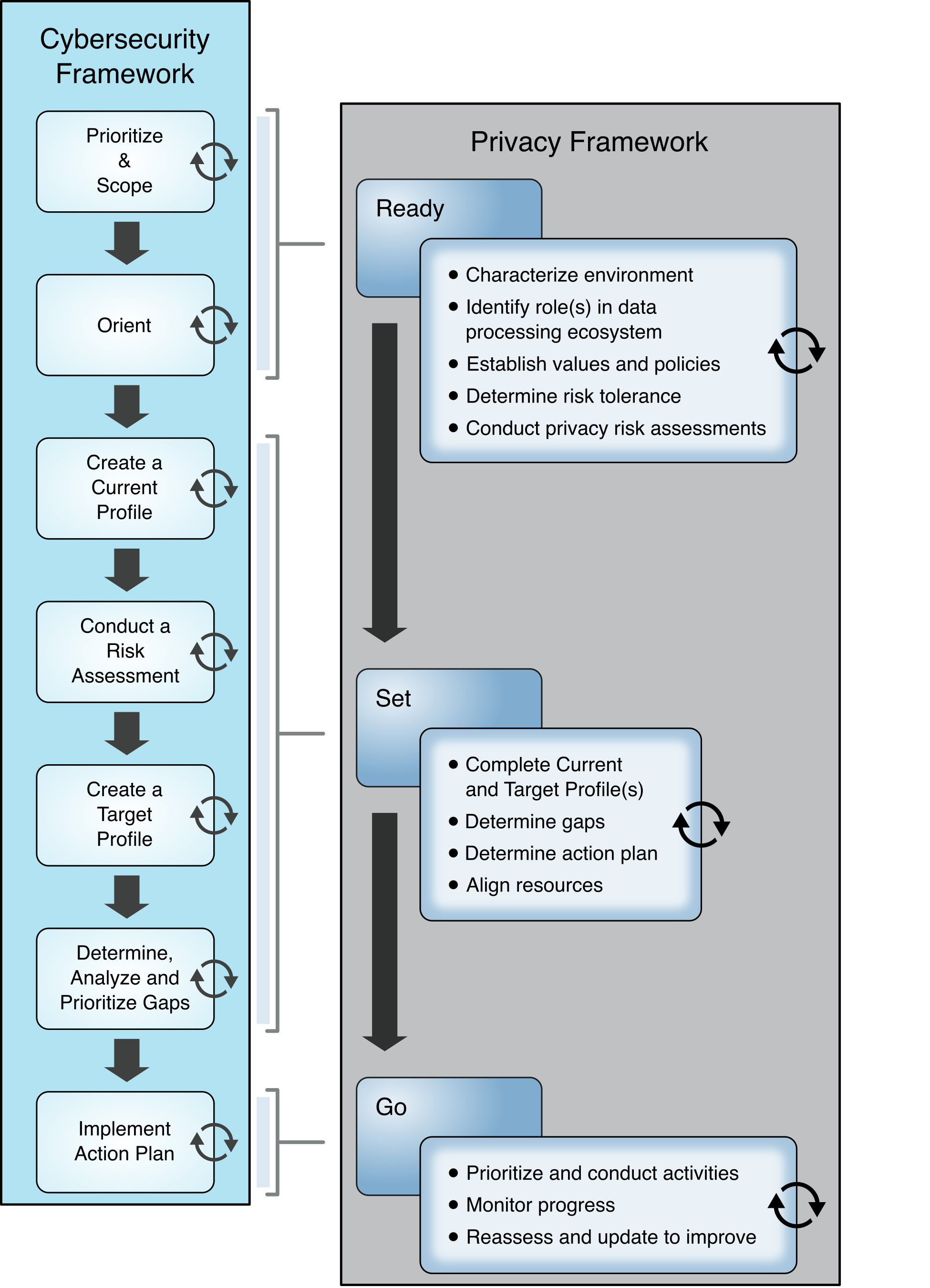

While their presentation differs, the NIST Cybersecurity Framework and NIST Privacy Framework also both provide complementary guidance for establishing and improving cybersecurity and privacy programs. The NIST Cybersecurity Framework’s process for establishing or improving programs provides seven steps that an organization could use iteratively and as necessary throughout the program’s life cycle to continually improve its cybersecurity posture:

Step 1: Prioritize and scope the organization’s mission.

Step 2: Orient its cybersecurity program activities to focus efforts on applicable areas.

Step 3: Create a current profile of what security areas it currently supports.

Step 4: Conduct a risk assessment.

Step 5: Create a Target Profile for the security areas that the organization would like to improve in the future.

Step 6: Determine, analyze, and prioritize cybersecurity gaps.

Step 7: Implement an action plan to close those gaps.

The NIST Privacy Framework includes the same types of activities for establishing and improving privacy programs, described in a three-stage Ready, Set, Go model. Figure E-1 below shows a comparison of these two approaches, demonstrating their close alignment.

Figure E‑1 Comparing Framework Processes to Establish or Improve Programs

Both approaches are equally effective. Regardless of the approach selected, an organization begins with orienting around its business/mission objectives and high-level organizational priorities and carry out the remaining activities in a way that makes the most sense for the organization. The organization repeats these steps as necessary throughout the program’s life cycle to continually improve its risk posture.

Appendix F How Great Seneca Accounting Used the NIST Risk Management Framework¶

This practice guide contains an example scenario about a fictional organization called Great Seneca Accounting. The example scenario shows how to deploy a Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) solution to be in alignment with an organization’s security and privacy capabilities and objectives.

The example scenario uses National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) standards, guidance, and tools. It is provided in the Example Scenario: Putting Guidance into Practice supplement of this practice guide.

In the example scenario supplement of this practice guide, Great Seneca Accounting decided to use the NIST Cybersecurity Framework, the NIST Privacy Framework, and the NIST Risk Management Framework to help improve its mobile device architecture. The following material provides information about how Great Seneca Accounting used the NIST Risk Management Framework to improve its BYOD deployment.

F.1 Understanding the Risk Assessment Process¶

This section provides information on the risk assessment process employed to improve the mobile security posture of Great Seneca Accounting. Typically, a risk assessment based on NIST SP 800-30 Revision 1 follows a four-step process as shown in Figure F-1: prepare for assessment, conduct assessment, communicate results, and maintain assessment.

Figure F‑1 Risk Assessment Process

F.2 Risk Assessment of Great Seneca Accounting’s BYOD Program¶

This risk assessment is scoped to Great Seneca Accounting’s mobile deployment, which includes the mobile devices used to access Great Seneca Accounting’s enterprise resources, along with any information technology components used to manage or provide services to those mobile devices.

Risk assessment assumptions and constraints were developed by using a NIST SP 800-30 Revision 1 generic risk model as shown in Figure F-2 to identify the following components of the risk assessment:

threat sources

threat events

vulnerabilities

predisposing conditions

security controls

adverse impacts

organizational risks

Figure F‑2 NIST SP 800-30 Generic Risk Model

F.3 Development of Threat Event Descriptions¶

Great Seneca Accounting developed threat event tables based on NIST SP 800-30 Revision 1 and used those to help analyze the sources of mobile threats. Using this process, Great Seneca Accounting leadership identified the following potential mobile device threat events that are described in the following subsections.

A note about selection of the threat events:

This practice guide’s example solution helps protect organizations from the threat events shown in Table F‑1. A mapping of these threat events to the NIST Mobile Threat Catalogue is provided in Table F-2.

Table F‑1 Great Seneca Accounting’s BYOD Deployment Threats

Great Seneca Accounting’s Threat Event Identification Number |

Threat Event Description |

|---|---|

TE-1 |

privacy-intrusive applications |

TE-2 |

account credential theft through phishing |

TE-3 |

malicious applications |

TE-4 |

outdated phones |

TE-5 |

camera and microphone remote access |

TE-6 |

sensitive data transmissions |

TE-7 |

brute-force attacks to unlock a phone |

TE-8 |

protection against weak password practices |

TE-9 |

protection against unmanaged devices |

TE-10 |

protection against lost or stolen data |

TE-11 |

protecting data from being inadvertently backed up to a cloud service |

TE-12 |

protection against sharing personal identification number (PIN) or password |

Great Seneca Accounting’s 12 threat events and their mapping to the NIST Mobile Threat Catalogue [S5] are shown in Table F‑2.

Table F‑2 Threat Event Mapping to the Mobile Threat Catalogue

Great Seneca Accounting’s Threat Event Identification Number |

NIST Mobile Threat Catalogue Threat ID |

|---|---|

TE-1 |

APP-2, APP-12 |

TE-2 |

AUT-9 |

TE-3 |

APP-2, APP-5, APP-31, APP-40, APP-32, AUT-10 |

TE-4 |

APP-4, APP-26, STA-0, STA-9, STA-16 |

TE-5 |

APP-32, APP-36 |

TE-6 |

APP-0, CEL-18, LPN-2 |

TE-7 |

AUT-2, AUT-4 |

TE-8 |

APP-9, AUT-0 |

TE-9 |

EMM-5 |

TE-10 |

PHY-0 |

TE-11 |

EMM-9 |

TE-12 |

AUT-0, AUT-2, AUT-4, AUT-5 |

F.4 Great Seneca Accounting’s Leadership and Technical Teams Discuss BYOD’s Potential Threats to Their Organization¶

Great Seneca Accounting’s leadership team wanted to understand real-world examples of each threat event and what the risk was for each. Great Seneca Accounting’s leadership and technical teams then discussed those possible threats that BYOD could introduce to their organization.

The analysis performed by Great Seneca Accounting’s technical team included analyzing the likelihood of each threat, the level of impact, and the threat level that the BYOD deployment would pose. The following are leadership’s questions and the technical team’s responses regarding BYOD threats during that discussion using real-world examples. One goal of the example solution contained within this practice guide is to mitigate the impact of these threat events. Reference Table 5-1 in Volume B for a listing of the technology that addresses each of the following threat events.

F.4.1 Threat Event 1¶

What happens if an employee installs risky applications?

A mobile application can attempt to collect and exfiltrate any information to which it has been granted access. This includes any information generated during use of the application (e.g., user input), user-granted permissions (e.g., contacts, calendar, call logs, photos), and general device data available to any application (e.g., International Mobile Equipment Identity, device make and model, serial number). Further, if a malicious application exploits a vulnerability in other applications, the operating system (OS), or device firmware to achieve privilege escalation, it may gain unauthorized access to any data stored on or otherwise accessible through the device.

Risk assessment analysis:

Overall likelihood: very high

Justification: Employees have access to download any application at any time. If an employee requires an application that provides a desired function, the employee can download that application from any available source (trusted or untrusted) that provides a desired function. If an application performs an employee’s desired function, the employee may download an application from an untrusted source and/or disregard granted privacy permissions.

Level of impact: high

Justification: Employees may download an application from an untrusted source and/or disregard granted privacy permissions. This poses a threat for sensitive corporate data, as some applications may include features that could access corporate data, unbeknownst to the user.

BYOD-specific threat: In a BYOD scenario, users are still able to download and install applications at their leisure. This capability allows users to unintentionally side-load or install a malicious application that may harm the device or the enterprise information on the device.

F.4.2 Threat Event 2¶

Can account information be stolen through phishing?

Malicious actors may create fraudulent websites that mimic the appearance and behavior of legitimate ones and entice users to authenticate to them by distributing phishing messages over short message service (SMS) or email. Effective social engineering techniques such as impersonating an authority figure or creating a sense of urgency may compel users to forgo scrutinizing the message and proceed to authenticate to the fraudulent website; it then captures and stores the userʼs credentials before (usually) forwarding them to the legitimate website to allay suspicion.

Risk assessment analysis:

Overall likelihood: very high

Justification: Phishing campaigns are a very common threat that occurs almost every day.

Level of impact: high

Justification: A successful phishing campaign could provide the malicious actor with corporate credentials, allowing access to sensitive corporate data, or personal credentials that could lead to compromise of corporate data or infrastructure via other means.

BYOD-specific threat: The device-level controls applied to personal devices do not inhibit a user’s activities. This allows the user to access personal/work messages and emails on their device that could be susceptible to phishing attempts. If the proper controls are not applied to a user’s enterprise messages and email, successful phishing attempts could allow an attacker unauthorized access to enterprise data.

F.4.3 Threat Event 3¶

How much risk do malicious applications pose to Great Seneca Accounting?

Malicious actors may send users SMS or email messages that contain a uniform resource locator (URL) where a malicious application is hosted. Generally, such messages are crafted using social engineering techniques designed to dissuade recipients from scrutinizing the nature of the message, thereby increasing the likelihood that they access the URL using their mobile device. If they do, it will attempt to download and install the application. Effective use of social engineering by the attacker will further compel an otherwise suspicious user to grant any trust required by the developer and all permissions requested by the application. Granting the former facilitates installation of other malicious applications by the same developer, and granting the latter increases the potential for the application to do direct harm.

Risk assessment analysis:

Overall likelihood: high

Justification: Installation of malicious applications via URLs is less common than other phishing attempts. The process for side-loading applications requires much more user input and consideration (e.g., trusting the developer certificate) than standard phishing, which solely requests a username and password. A user may proceed through sideloading an application to acquire a desired capability from an application.

Level of impact: high

Justification: Once a user installs a malicious side-loaded application, an adversary could gain full access to a mobile device and, therefore, access to corporate data and credentials, without the user’s knowledge.

BYOD-specific threat: Like threat event 1, BYOD deployments may have fewer restrictions to avoid preventing the user from performing desired personal functions. This increases the attack surface for malicious actors to take advantage.

F.4.4 Threat Event 4¶

What happens when outdated phones access Great Seneca Accounting’s network?

When malware successfully exploits a code execution vulnerability in the mobile OS or device drivers, the delivered code generally executes with elevated privileges and issues commands in the context of the root user or the OS kernel. This may be enough for some malicious actors to accomplish their goal, but those that are advanced will usually attempt to install additional malicious tools and to establish a persistent presence. If successful, the attacker will be able to launch further attacks against the user, the device, or any other systems to which the device connects. As a result, any data stored on, generated by, or accessible to the device at that time or in the future may be compromised.

Risk assessment analysis:

Overall likelihood: high

Justification: Many public vulnerabilities specific to mobile devices have been seen over the years. In these, users can jailbreak iOS devices and root Android devices to download third-party applications and apply unique settings/configurations that the device would not typically be able to apply/access.

Level of impact: high

Justification: Exploiting a vulnerability allows circumventing security controls and modifying protected device data that should not be modified. Jailbroken and rooted devices exploit kernel vulnerabilities and allow third-party applications/services root access that can also be used to bypass security controls that are built in or applied to a mobile device.

BYOD-specific threat: As with any device, personal devices are susceptible to device exploitation if not properly used or updated.

F.4.5 Threat Event 5¶

Can Great Seneca Accounting stop someone from turning on a camera or microphone?

Malicious actors with access (authorized or unauthorized) to device sensors (microphone, camera, gyroscope, Global Positioning System receiver, and radios) can use them to conduct surveillance. It may be directed at the user, as when tracking the device location, or it may be applied more generally, as when recording any nearby sounds. Captured sensor data may be immediately useful to a malicious actor, such as a recording of an executive meeting. Alternatively, the attacker may analyze the data in isolation or in combination with other data to yield sensitive information. For example, a malicious actor can use audio recordings of on-device or proximate activity to probabilistically determine user inputs to touchscreens and keyboards, essentially turning the device into a remote keylogger.

Risk assessment analysis:

Overall likelihood: very high

Justification: This has been seen on public application stores, with applications allegedly being used for data-collection. As mentioned in threat event 1, unbeknownst to the user, a downloaded application may be granted privacy-intrusive permissions that allow access to device sensors.

Level of impact: high

Justification: When the sensors are being misused, the user is typically not alerted. This allows collection of sensitive enterprise data, such as location, without knowledge of the user.

BYOD-specific threat: Applications commonly request access to these sensors. In a BYOD deployment, the enterprise does not have control over what personal applications the user installs on their device. These personal applications may access sensors on the device and eavesdrop on a user’s enterprise-related activities (e.g., calls and meetings).

F.4.6 Threat Event 6¶

Is sensitive information protected when the data travels between the employee’s mobile device and Great Seneca Accounting’s network?

Malicious actors can readily eavesdrop on communication over unencrypted, wireless networks such as public Wi-Fi access points, which coffee shops and hotels commonly provide. While a device is connected to such a network, a malicious actor could gain unauthorized access to any data sent or received by the device for any session that has not already been protected by encryption at either the transport or application layers. Even if the transmitted data were encrypted, an attacker would be privy to the domains, internet protocol (IP) addresses, and services (as indicated by port numbers) to which the device connects; an attacker could use such information in future watering hole or person-in-the-middle attacks against the device user.

Additionally, visibility into network-layer traffic enables a malicious actor to conduct side-channel attacks against the network’s encrypted messages, which can still result in a loss of confidentiality. Further, eavesdropping on unencrypted messages during a handshake to establish an encrypted session with another host or endpoint may facilitate attacks that ultimately compromise the security of the session.

Risk assessment analysis:

Overall likelihood: moderate

Justification: Unlike installation of an application, installations of enterprise mobility management (EMM)/mobile device management (MDM), network, virtual private network (VPN) profiles, and certificates require additional effort and understanding from the user to properly implement.

Level of impact: very high

Justification: If a malicious actor can install malicious configuration profiles or certificates, they would be able to perform actions such as decrypting network traffic and possibly even control the device.

BYOD-specific threat: Like threat event 2, personal devices may not have the benefit of an always-on device-wide VPN. This leaves application communications at the discretion of the developer.

F.4.7 Threat Event 7¶

Is Great Seneca Accounting’s data protected from brute-force PIN attacks?

A malicious actor may be able to obtain a user’s device unlock code by direct observation, side-channel attacks, or brute-force attacks. Both the first and second can be attempted with at least proximity to the device; only the third technique requires physical access. However, applications with access to any peripherals that detect sound or motion (microphone, gyroscope, or accelerometer) can attempt side-channel attacks that infer the unlock code by detecting taps and swipes to the screen. Once the device unlock code has been obtained, a malicious actor with physical access to the device will gain immediate access to any data or functionality not already protected by additional access control mechanisms. Additionally, if the user employs the device unlock code as a credential to any other systems, the malicious actor may further gain unauthorized access to those systems.

Risk assessment analysis:

Overall likelihood: moderate

Justification: Unlike shoulder-surfing to observe a user’s passcode, brute-force attacks are not as common or successful due to the built-in deterrent mechanisms. These mechanisms include exponential back-off/lockout period and device wipes after a certain number of failed unlock attempts.

Level of impact: very high

Justification: If a malicious actor can successfully unlock a device without the user’s permission, they could have full control over the user’s corporate account and, thus, gain unauthorized access to corporate data.

BYOD-specific threat: Because BYODs are prone to travel (e.g., vacations, restaurants, and other nonwork locations), the risk that the device’s passcode is obtained increases due to the heightened exposure to threats in different environments.

F.4.8 Threat Event 8¶

Can Great Seneca Accounting protect its data from poor application development practices?

If a malicious actor gains unauthorized access to a mobile device, they also have access to the data and applications on that mobile device. The mobile device may contain an organization’s in-house applications that a malicious actor can subsequently use to gain access to sensitive data or backend services. This could result from weaknesses or vulnerabilities present in the authentication or credential storage mechanisms implemented within an in-house application.

Risk assessment analysis:

Overall likelihood: moderate

Justification: Often applications include hardcoded credentials for the default password of the admin account. Default passwords are readily available online. The user might not change these passwords to allow access and eliminate the need to remember a password.

Level of impact: high

Justification: Successful extraction of the credentials allows an attacker to gain unauthorized access to enterprise data.

BYOD-specific threat: The risk of hardcoded credentials residing in an application on the device is the same for any mobile device deployment scenario.

F.4.9 Threat Event 9¶

Can unmanaged devices connect to Great Seneca Accounting?

An employee who accesses enterprise resources from an unmanaged mobile device may expose the enterprise to vulnerabilities that may compromise enterprise data. Unmanaged devices do not benefit from any security mechanisms deployed by the organization such as mobile threat defense, mobile threat intelligence, application vetting services, and mobile security policies. These unmanaged devices limit an organization’s visibility into the state of a mobile device, including if a malicious actor compromises the device. Therefore, users who violate security policies to gain unauthorized access to enterprise resources from such devices risk providing malicious actors with access to sensitive organizational data, services, and systems.

Risk assessment analysis:

Overall likelihood: very high

Justification: This may occur accidentally when an employee attempts to access their email or other corporate resources.

Level of impact: high

Justification: Unmanaged devices pose a sizable security risk because the enterprise has no visibility into their security or risk postures of the mobile devices. Due to this lack of visibility, a compromised device may allow an attacker to attempt to exfiltrate sensitive enterprise data.

BYOD-specific threat: The risk of an unmanaged mobile device accessing the enterprise is the same for any mobile deployment scenario.

F.4.10 Threat Event 10¶

Can Great Seneca Accounting protect its data when a phone is lost or stolen?

Due to the nature of the small form factor of mobile devices, they can be misplaced or stolen. A malicious actor who gains physical custody of a device with inadequate security controls may be able to gain unauthorized access to sensitive data or resources accessible to the device.

Risk assessment analysis:

Overall likelihood: very high

Justification: Mobile devices are small and can be misplaced. Enterprise devices may be lost or stolen at the same frequency as personally owned devices.

Level of impact: high

Justification: Similar to threat event 9, if a malicious actor can gain access to the device, they could access sensitive corporate data.

BYOD-specific threat: Due to the heightened mobility of BYODs, they are more prone to being accidentally lost or stolen.

F.4.11 Threat Event 11¶

Can data be protected from unauthorized cloud services?

If employees violate data management policies by using unmanaged services to store sensitive organizational data, the data will be placed outside organizational control, where the organization can no longer protect its confidentiality, integrity, or availability. Malicious actors who compromise the unauthorized service account or any system hosting that account may gain unauthorized access to the data.

Further, storage of sensitive data in an unmanaged service may subject the user or the organization to prosecution for violation of any applicable laws (e.g., exportation of encryption) and may complicate efforts by the organization to achieve remediation or recovery from any future losses, such as those resulting from public disclosure of trade secrets.

Risk assessment analysis:

Overall likelihood: high

Justification: This could occur either intentionally or accidentally (e.g., taking a screenshot and having pictures backed up to an unmanaged cloud service).

Level of impact: high

Justification: Storage in unmanaged services presents a risk to the confidentiality and availability of corporate data because the corporation would no longer control it.

BYOD-specific threat: In a BYOD deployment, employees are more likely to have some backup or automated cloud storage solution configured on their device, which may lead to unintentional backup of enterprise data.

F.4.12 Threat Event 12¶

Can Great Seneca Accounting protect its data from PIN or password sharing?

Many individuals choose to share the PIN or password to unlock their personal device with family members. This creates a scenario where a non-employee can access the device, the work applications, and, therefore, the work data.

Risk assessment analysis:

Overall likelihood: moderate

Justification: Even though employees are conditioned almost constantly to protect their work passwords, personal device PINs and passwords are not always protected with that same level of security. Anytime individuals share a password or PIN, there is an increased risk that it might be exposed or compromised.

Level of impact: very high

Justification: If a malicious actor can bypass a device lock and gain access to the device, they can potentially access sensitive corporate data.

BYOD-specific threat: The passcode of an individual’s personal mobile device is more likely to be shared among family and/or friends to provide access to applications (e.g., games). Although sharing passcodes may be convenient for personal reasons, this increases the risk of an unauthorized individual gaining access to enterprise data through a personal device.

F.5 Identification of Vulnerabilities and Predisposing Conditions¶

In this section we identify vulnerabilities and predisposing conditions that increase the likelihood that identified threat events will result in adverse impacts for Great Seneca Accounting. We list each vulnerability or predisposing condition in Table F-3, along with the corresponding threat events and ratings of threat pervasiveness. More details on threat event ratings can be found in Appendix Section F-3.

Table F‑3 Identify Vulnerabilities and Predisposing Conditions

Vulnerability ID |

Vulnerability or Predisposing Condition |

Resulting Threat Events |

Pervasiveness |

|---|---|---|---|

VULN-1 |

Email and other enterprise resources can be accessed from anywhere, and only username/password authentication is required. |

TE-2, TE-9, TE-10 |

very high |

VULN-2 |

Public Wi-Fi networks are regularly used by employees for remote connectivity from their mobile devices. |

TE-6 |

very high |

VULN-3 |

No EMM/MDM deployment exists to enforce and monitor compliance with security-relevant policies on mobile devices. |

TE-1, TE-3, TE-4, TE-5, TE-6, TE-7, TE-8, TE-9, TE-10, TE-11, TE-12 |

very high |

F.6 Summary of Risk Assessment Findings¶

Table F‑4 summarizes the risk assessment findings. More detail about the methodology used to rate overall likelihood, level of impact, and risk is in the Appendix Section F.3.

Table F‑4 Summary of Risk Assessment Findings

Threat Event |

Vulnerabilities, Predisposing Conditions |

Overall Likelihood |

Level of Impact |

Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

TE-1: unauthorized access to sensitive information via a malicious or privacy-intrusive application |

VULN-3 |

very high |

high |

high |

TE-2: theft of credentials through an SMS or email phishing campaign |

VULN-1 |

very high |

high |

high |

TE-3: malicious applications installed via URLs in SMS or email messages |

VULN-3 |

high |

high |

high |

TE-4: confidentiality and integrity loss due to exploitation of known vulnerability in the OS or firmware |

VULN-3 |

high |

high |

high |

TE-5: violation of privacy via misuse of device sensors |

VULN-3 |

very high |

high |

high |

TE-6: loss of confidentiality of sensitive information via eavesdropping on unencrypted device communications |

VULN-2, VULN-3 |

moderate |

very high |

high |

TE-7: compromise of device integrity via observed, inferred, or brute-forced device unlock code |

VULN-3 |

moderate |

very high |

high |

TE-8: unauthorized access to backend services via authentication or credential storage vulnerabilities in internally developed applications |

VULN-3 |

moderate |

high |

high |

TE-9: unauthorized access of enterprise resources from an unmanaged and potentially compromised device |

VULN-1, VULN-3 |

very high |

high |

high |

TE-10: loss of organizational data due to a lost or stolen device |

VULN-1, VULN-3 |

very high |

high |

high |

TE-11: loss of confidentiality of organizational data due to its unauthorized storage in non-organizationally managed services |

VULN-3 |

high |

high |

high |

TE-12: unauthorized access to work applications via bypassed lock screen |

VULN-3 |

moderate |

very high |

high |

Note 1: Risk is stated in qualitative terms based on the scale in Table I-2 of Appendix I in NIST SP 800-30 Revision 1 [S8].

Note 2: The risk rating is derived from both the overall likelihood and level of impact using Table I-2 of Appendix I in NIST SP 800-30 Revision 1 [S8]. Because these are modified interval scales, the combined overall risk ratings from Table I-2 do not always reflect a strict mathematical average of these two variables. The table above demonstrates this where levels of moderate weigh more heavily than other ratings.

Note 3: Ratings of risk relate to the probability and level of adverse effect on organizational operations, organizational assets, individuals, other organizations, or the nation. Per NIST SP 800-30 Revision 1, adverse effects (and the associated risks) range from negligible (i.e., very low risk), limited (i.e., low), serious (i.e., moderate), severe or catastrophic (i.e., high), to multiple severe or catastrophic (i.e., very high).

Appendix G How Great Seneca Accounting Used the NIST Privacy Risk Assessment Methodology¶

This practice guide contains an example scenario about a fictional organization called Great Seneca Accounting. The example scenario shows how to deploy a Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) solution to be in alignment with an organization’s security and privacy capabilities and objectives.

The example scenario uses National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) standards, guidance, and tools.

In the example scenario, Great Seneca Accounting decided to use the NIST Privacy Risk Assessment Methodology (PRAM) to conduct a privacy risk assessment and help improve the company’s mobile device architecture. The PRAM helps an organization analyze and communicate about how it conducted its data processing to achieve business/mission objectives.

At Great Seneca Accounting, the PRAM helped elucidate how enabling employees to use their personal devices for work-related functions can present privacy concerns for individuals. The PRAM also supports the risk assessment task in the Prepare step of the NIST Risk Management Framework as discussed in Appendix Section E.1. The privacy events that were identified are provided below, along with potential mitigations.

G.1 Privacy Risk 1: Wiping Activities on the User’s Device May Inadvertently Delete the User’s Personal Data¶

Privacy Risk: Removal of personal data from a device.

Potential Problem for Individuals: In a BYOD environment, employees are likely to use their devices for both personal and work-related purposes; thus, in a system that features robust security information and event management capable of wiping a device entirely, there could be an issue of employees losing personal data and employees may not even expect that this is a possibility. A hypothetical example is that a Great Seneca Accounting employee stores personal photos on their mobile device within the work container, but these photos are lost when their device is selectively wiped after anomalous activity is detected. This privacy risk is related to the Unwarranted Restriction Problematic Data Action.

Mitigations:

Block access to corporate resources by removing the device from mobile device management (MDM) control instead of wiping devices.

As an alternative to wiping data entirely, Section F.4.3, Threat Event 3, discusses blocking a device from accessing enterprise resources until an application is removed. Temporarily blocking access ensures that an individual will not lose personal data through a full wipe of a device. This approach may help bring the system’s capabilities into alignment with employees’ expectations about what can happen to their devices, especially if they are unaware that devices can be wiped by administrators, providing greater predictability in the system.

Related mitigation: If this mitigation approach is taken, the organization may also wish to consider establishing and communicating these remediation processes to employees. It is important to have a clear remediation process in place to help employees regain access to resources on their devices at the appropriate time. It is also important to clearly convey this remediation process to employees. A remediation process provides greater manageability in the system supporting employees’ ability to access resources. If well-communicated to employees, this also provides greater predictability as employees will know the steps to regain access.

Enable only selective wiping of corporate resources on the device.

An alternative mitigation option for wiping device data is to limit what can be wiped. International Business Machines’ (IBM’s) MaaS360 can be configured to selectively wipe instead of performing a full factory reset. When configured this way, a wipe preserves employees’ personal configurations, applications, and data while removing only the corporate configurations, applications, and data. However, on Android, a selective wipe will preserve restrictions imposed via policy on the device. To fully remove MDM control, the Remove Work Profile action must be used.

Advise employees to appropriately store and back up the personal data maintained on devices.

If device wiping remains an option for administrators, encourage employees to perform regular backups of their personal data to ensure it remains accessible in case of a wipe and to not store personal data within the work container on their device.

Restrict staff access to system capabilities that permit removing device access or performing wipes.

Limit staff with the ability to perform a wipe to only those with that responsibility by using role-based access controls. This can help decrease the chances of accidentally removing employee data or blocking access to resources.

G.2 Privacy Risk 2: Organizational Collection of Device Data May Subject Users to Feeling or Being Surveilled¶

Privacy Risk: The assessed infrastructure offers Great Seneca Accounting and its employees a number of security capabilities, including reliance on comprehensive monitoring capabilities, as noted in Volume B Section 4, Architecture. Multiple parties could collect and analyze a significant amount of data relating to employees, their devices, and their activities.

Potential Problem for Individuals: Employees may not be aware that the organization has the ability to monitor their interactions with the system and may not want this monitoring to occur or understand the way these interactions are being analyzed or used. If there is awareness, employees may feel compelled to allow for monitoring to occur for the ability to use their mobile devices for corporate access. Collection and analysis of information might enable Great Seneca Accounting or other parties to craft a narrative about an employee based on the employee’s interactions with the system, which could lead to a power imbalance between Great Seneca Accounting and the employee and loss of trust in the employer or loss of autonomy if the employee discovers monitoring that they did not anticipate or expect. This privacy risk is related to the Surveillance Problematic Data Action.

Mitigations:

Restrict staff access to system capabilities that permit reviewing data about employees and their devices.

This may be achieved using role-based access controls. Access can be limited to any dashboard in the system containing data about employees and their devices but is most sensitive for the MaaS360 dashboard, which is the hub for data about employees, their devices, and threats. Minimizing access to sensitive information can enhance disassociability for employees using the system.

Limit or disable collection of specific data elements.

Conduct a system-specific privacy risk assessment to determine what elements can be limited. In the configuration of MaaS360, location services and application inventory collection may be disabled. iOS devices can be configured in MaaS360 to collect only an inventory of applications that have been installed through the corporate application store instead of all applications installed on the device.

While these administrative configurations may help provide disassociability in the system, there are also some opportunities for employees to limit the data collected. Employees can choose to disable location services in their device OS to prevent collection of location data. MaaS360 can also be configured to provide employees with the ability to manage their own devices through the IBM User Portal.

Each of these controls contributes to limiting the number of attributes regarding employees and their devices that is collected, which can impede administrators’ ability to associate information with specific individuals.

Dispose of personally identifiable information (PII).

Disposing of PII after an appropriate retention period can help reduce the risk of entities building profiles of individuals. Disposal can also help bring the system’s data processing into alignment with employees’ expectations and reduce the security risk associated with storing a large volume of PII. Disposal may be particularly important for certain parties in the system that collect a larger volume of data or more sensitive data. Disposal may be achieved using a combination of policy and technical controls. Parties in the system may identify what happens to data, when, and how frequently.

G.3 Privacy Risk 3: Data Collection and Transmission Between Integrated Security Products May Expose User Data¶

Privacy Risk: The infrastructure involves several parties that serve different purposes supporting Great Seneca Accounting’s security objectives. As a result, device usage information could flow across various parties.

Potential Problems for Individuals: This transmission among a variety of different parties could be confusing for employees who might not know who has access to information about them. If administrators and co-workers know which colleagues are conducting activity on their device that triggers security alerts, employees could be embarrassed by its disclosure. Information being revealed and associated with specific employees could also lead to stigmatization and even impact Great Seneca Accounting upper management in its decision-making regarding the employee. Further, clear text transmissions could leave information vulnerable to attackers and, therefore, to an unanticipated release of employee information. This privacy risk is related to the Unanticipated Revelation Problematic Data Action.

Mitigations:

De-identify personal and device data when that data is not necessary to meet processing objectives.

De-identifying data helps decrease the chances that a third party is aggregating information pertaining to one individual. While de-identification can help reduce privacy risk, there are residual risks of re-identification.

Encrypt data transmitted between parties.

Encryption reduces the risk of compromise of information transmitted between parties. MaaS360 encrypts all communications over the internet with Transport Layer Security.

Limit or disable access to data.

Conduct a system-specific privacy risk assessment to determine how access to data can be limited. Using access controls to limit staff access to compliance information, especially when associated with individuals, can be important in preventing association of specific events with specific employees.

Limit or disable collection of specific data elements.

Conduct a system-specific privacy risk assessment to determine what elements can be limited. MaaS360 can be configured to limit collection of application and location data. Further, instead of collecting a list of all the applications installed on the device, MaaS360 can collect only the list of those applications that were installed through the corporate application store (called “managed applications”). This would prevent insight into the employees’ applications that employees downloaded for personal use. Zimperium provides privacy policies that can be configured to collect or not collect data items when certain events occur.

Use contracts to limit third-party data processing.

Establish contractual policies to limit data processing by third parties to only the processing that facilitates delivery of security services and to no data processing beyond those explicit purposes.

G.4 Mitigations Applicable Across Various Privacy Risks¶

Several mitigations benefit employees in all three privacy risks identified in the privacy risk assessment. The following training and support mitigations can help Great Seneca Accounting appropriately inform employees about the system and its data processing.

Mitigations:

Train employees about the system, parties involved, data processing, and actions that administrators can take.

Training sessions can also highlight any privacy-preserving techniques used, such as for disclosures to third parties. Training should include confirmation from employees that they understand the actions that administrators can take on their devices and their consequences—whether this is blocking access or wiping data. Employees may also be informed of data retention periods and when their data will be deleted. This can be more effective than sharing a privacy notice, which research has shown, individuals are unlikely to read. Still, MaaS360 should also be configured to provide employees with access to a visual privacy policy, which describes what device information is collected and why, as well as what actions administrators can take on the device. This enables employees to make better informed decisions while using their devices, and it enhances predictability.

Provide ongoing notifications or reminders about system activity.

This can be achieved using notifications to help directly link administrative actions on devices to relevant threats and to also help employees understand why an action is being taken. MaaS360 also notifies employees when changes are made to the privacy policy or MDM profile settings. These notifications can help increase system predictability by setting employee expectations appropriately regarding the way the system processes data and the resulting actions.

Provide a support point of contact.

By providing employees with a point of contact in the organization who can respond to inquiries and concerns regarding the system, employees can better understand how the system processes their data, which enhances predictability.

G.5 Privacy References for Example Solution Technologies¶

Additional privacy information on the example solution’s technologies appears below.

Table G‑1 Privacy References for the Example Solution Technologies

Commercially Available Product |

Mobile Security Technology |

Product Privacy Information Location |

|---|---|---|

IBM MaaS360 Mobile Device Management (SaaS) Version 10.73 IBM MaaS360 Mobile Device Management Agent Version 3.91.5 (iOS), 6.60 (Android) IBM MaaS360 Cloud Extender / Cloud Extender Modules |

mobile device management |

https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/search/privacy https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/node/571227 https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/maas360-data-privacy-information |

Kryptowire Cloud Service |

application vetting |

|

Palo Alto Networks PA-VM-100 Version 9.0.1 Palo Alto Networks GlobalProtect VPN Client Version 5.0.6-14 (iOS), 5.0.2-6 (Android) |

virtual private network (VPN) and firewall/ filtering |

https://www.paloaltonetworks.com/resources/datasheets/url-filtering-privacy-datasheet |

Qualcomm (Version is mobile device dependent) |

trusted execution environment |

|

Zimperium Defense Suite Zimperium Console Version vGA-4.23.1 Zimperium zIPS Agent Version 4.9.2 (Android and iOS) |

mobile threat defense |